Silicon Valley Could Be The Answer For California’s Prisons

Kenyatta Leal and the Last Mile are reducing recidivism by training offenders for a life in tech, not prison. So far, not one person has dropped out of the organization.

As we’ve illustrated previously in our criminal justice series, the United States has a serious recidivism problem. State prisons in the US had a five-year recidivism rate of over 76% in 2016.

Theoretically the prison system has four main roles; retribution, incapacitation, deterrence and rehabilitation. The last of these seems to have been forgotten in today’s system. In fact it doesn’t appear to be a priority at all.

Unlike most other nations, the United States’ Department of Justice has no mention of offender rehabilitation in its mission statement.

Its sole stated goal for offenders is “to seek just punishment for those guilty of unlawful behavior.”

In the absence of a concerted nation-wide commitment to reducing recidivism, the onus often falls on state governments and individual programs.

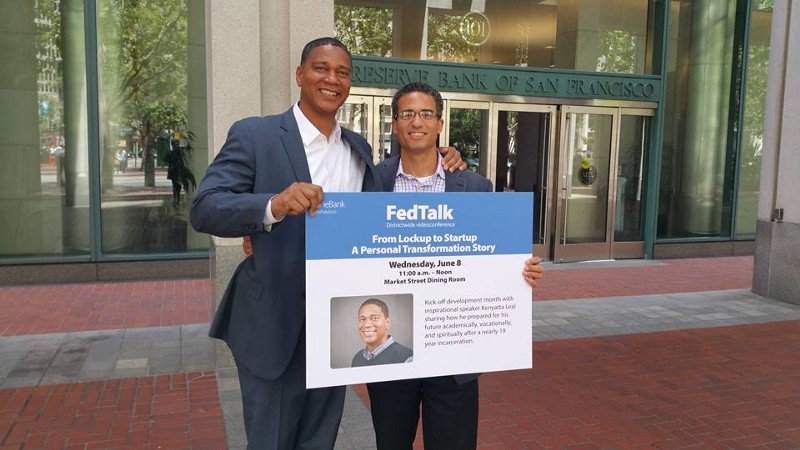

Kenyatta Leal. Photo Courtesy of Subject

Kenyatta Leal and The Last Mile, a Bay Area organization, are helping incarcerated individuals get business and technical training for jobs in tech. In the process, they might just help fulfill Silicon Valley’s tech shortfall.

Not Just Any Job Will Do

There is a wealth of evidence supporting the link between employment and reduced rates of recidivism [1][2]. Employment, along with education and job training, is one of the most requested re-entry needs of offenders.

But a job is not a silver-bullet for beating recidivism.

Most ex-prisoners find themselves leaving incarceration less employable than before they went in. They’ve been out of the workforce a long time and many lack the skills, experience or confidence to enter higher quality jobs. On top of all that is the stigma attached to being an ex-con.

Often ex-offenders end up in temporary and low wage jobs. But evidence suggests that the jobs with a real ability to curb offenders’ recidivism rates are high-quality, stable jobs.

While serving a life sentence under California’s three strikes law, Kenyatta Leal saw first-hand how easy it is to end up back in prison post-release.

In response to this, he and the team at The Last Mile are setting up prisoners with the skills needed to enter one of the most rapidly growing job markets— the tech industry.

So far, their recidivism rate is 0.

When Kenyatta Leal was sentenced to life behind bars at 25, he had never used the Internet. Now, he teaches inmates in similar situations how to code. The Last Mile’s Code.7370 is the United States’ first behind-bars coding curriculum.

Mr. Leal, Photo Courtesy The Last Mile

Introducing Mr. Leal

Growing up in California in a single parent household, Kenyatta Leal struggled with the absence of his father.

“I grew up you know with kinda like this hole in my heart, you know, wishing that my father was there and hoping that he would come back, ” he explains. “But he never did.”

He continues, “I didn’t know how to reconcile that in my own mind, in my own heart, as a young person. I grew up trying to find external things to fill this internal void that I had in my heart.”

After dropping out of school in the 11th grade, Leal started to hang out with a different crowd. He began selling drugs, and as he continued to try and fit in, his criminal behaviour escalated.

In 1991, Leal was convicted of armed robbery, and sentenced to five years in state prison. But Leal’s time behind bars in the state prison did little to change his behaviour upon re-release.

“I didn’t utilize that time to take responsibility for the crimes that I had committed, or the harm that I created in my community. I basically got out of prison with the same mindset that I went in with,” he says.

It was bad timing.

Just before Leal left prison in 1994, California had passed its three strikes law: anyone receiving a third felony conviction would automatically also receive a life sentence.

Unaware that he already had two strikes to his name, Leal went right back to the same crowd, same activity. Within five months, he was pulled over on a routine traffic stop and his car was searched.

“They found a firearm in my car and I was sent to jail for being an ex-felon in the possession of a firearm,” he recalls. “I was later convicted and I was sentenced to 25 to life in prison.”

At the time of his sentencing, Leal was just 25. Now he faced spending at least the next 25 years of his life behind bars.

“Being faced with the prospect of spending the rest of my life in prison; that was never something that I dreamed could happen,” he admits. “I was involved in the illegal activity and all that, but I never I never thought that I would wind up in prison with a life sentence.”

“[Prison life] was a very eye-opening, sobering experience”.

Surrounded by violence and racial conflict inside prison, Leal realized that this was not what he had envisioned for himself. He was determined that, unlike his previous stint behind bars, this time he was going to change.

“I realized that this wasn’t the life for me. I knew that I wanted to change my life, I just didn’t know how,” he explains.

“I think probably the most important thing that I did when I was inside prison was learn to ask for help.”

There was no way, he explains, that he could have begun this change on his own.

“Let’s face it there’s no manual of how to change your life in prison. Prison is a very violent place, there’s all kinds of negative activity that’s taking place in there. It was difficult for me to to embark on that journey.”

Seeing Recidivism First Hand

Despite his life sentence, Leal maintains he always believed he would get out of prison. And when he did, he was going to make the most of it.

“I could always see this bright light at the end of the tunnel,” he explains, “I knew that I had to do what I needed to do to turn my life around.”

In California, where Leal was incarcerated, the recidivism rate is over 60%. This has changed little since Leal himself was behind bars.

“In my mind, getting out of prison and staying out of person were two different things,” he explains. “I didn’t want to increase that statistic. I wanted to turn that statistic around.”

Leal was well aware just how easy it was to end up back in prison. All around him were living examples of the cyclical nature of recidivism.

“There was a guy who was in incarcerated with me. He was serving a life sentence under the three strikes rule for being a heroin addict. He was still using heroin inside prison; he never got clean and sober,” he recalls.

“And he used to be a barber so he cut my hair all the time and would tell me all these stories about how he was going to find a loophole in the law and get out, and sure enough, he did. He used to go to the law library and he found a loophole in the law and he was able to get out of prison.”

“Within six months of his release, though, he was back in prison with a brand new life sentence. Sent back to the same prison, in the same yard, in the same cell. Back on the same bleachers cutting people’s hair again, telling the same stories all over again.”

Leal continues: “When I saw this guy, who had an opportunity to go home, come back with a new life sentence because of heroin again, it just let me know that you can get out. But if you don’t change your mind — if you don’t change your heart — you’re destined to come back to prison.”

“I didn’t want to repeat that cycle for myself. I saw with my own eyes how real it was.”

Leal was determined that if he ever got the chance to get out, he was going to be prepared for it. He threw himself into every educational and self-help program he could.

San Quentin and The Last Mile: the ‘Perfect Prison‘

In 2005, in the aftermath of race riots at Centinela State Prison where he was being held, Leal was transferred to San Quentin prison.

He describes the move as “a blessing in disguise:” while San Quentin is notorious for housing California’s death row inmates, it also has some of the best rehabilitative programs of any prison in the state.

“If you could imagine the perfect prison to be at, San Quentin was that for me. There were a lot of opportunities for me to better myself,” he says.

Through his deep dive into the prison’s programs Leal met husband and wife team, Beverly Parenti and Chris Redlitz, founders of The Last Mile.

“They came into San Quentin with this idea of starting a technology accelerator called The Last Mile, and I was selected as part of the first cohort,” Leal explains.

The Last Mile began as an entrepreneurship program, encouraging inmates to tap into their passions and create a business idea that included both a technology component and a social cause.

Participants work on their business and problem-solving skills and it all builds toward their graduation, or ‘demo-day’, where they get the opportunity to pitch their business ideas to members of the surrounding business community.

The catch is, however, many of the participants challenged with proposing technology-based business plans have never seen the internet before — Kenyatta included.

“When I went to prison in 1994, the internet wasn’t a big thing” he says. “I had never Googled anything. I never knew what Twitter was. I didn’t know anything about the internet until I got into The Last Mile.”

Early on in the program, Parenti and Redlitz started a system where inmates could tweet from prison. For Leal, this was a lightbulb moment.

“Chris and Beverly would bring in pieces of graph paper with 140 squares on them, and we would write out tweets and then give them to them,” he explains. “They would take them out and then upload them onto Twitter, then they would bring back in the responses that we were getting from people from the outside world.”

“That was amazing,” continues Leal. “Up until that point we didn’t have a voice. You know, people don’t listen to people in prison. They are not able to engage in like the public discourse; but The Last Mile actually gave us an avenue to do that.”

From their rudimentary Twitter system, the inmates moved on to writing blog posts on The Daily Love, and then to answering questions on Quora about life in the US prison system.

“A couple of guys from our program wrote really prolific stuff on there that got a bunch of attention out here in society,” says Leal, who himself won a Shorty award for one of his answers on the website.

From Entrepreneurs to Software Engineers

Four years ago The Last Mile shifted their focus toward software development with a new program called Code.7370.

Code.7370 is the first ever computer coding curriculum to be taught in a United States prison. Participants are taught HTML, JavaScript, CSS and Python, as well as data visualization and web development.

Only problem; there’s no Internet in prison.

“Anybody out here can just go online, find some free coding courses and take them right?” he says. “Inside prison, people don’t have connectivity. So what we did is built a proprietary system that allows people to learn how to code without this connectivity; it basically simulates a live coding experience.”

The decision to focus on software development was a strategic one, aimed at increasing the chances of graduates finding employment when they leave prison.

“A person having a job is a key component to breaking the cycle of incarceration,” explains Leal, ”so part of our mission is to provide marketable skills that lead to employment.”

If what they want is to find people stable, high-quality jobs, the burgeoning tech industry is a particularly good fit. It’s predicted that over 1 million tech jobs will be left unfilled by 2020. Leal hopes his fellow Last Mile graduates will be able to meet some of that need.

But beyond the logistics of the job market, the tech industry is, by nature, much more open to employing people leaving incarcerated settings, claims Leal.

“I work with entrepreneurs all the time and I’ve met so many CEOs and founders of tech startups,” he says. “One of the things that I always hear them say is that failure is not necessarily a bad thing. You can fail and then try again, learn from the mistakes and failures that you’ve made”

In this, Kenyatta sees a strong likeness between young tech entrepreneurs and Code.7370 graduates.

“There’s definitely a parallel between the two mindsets. I think that that’s why the program is so well received here in Silicon Valley,” he adds.

According to Leal, The Last Mile and Code.7370 currently boast a remarkable 0% recidivism rate and 100% employment rate among graduates.

“No people from our program have returned to prison,” he states proudly. “Not one.”

The program isn’t just for individuals coming to the end of their sentences. “Lifers” such as Leal are seen as valuable contributors to the program, acting as evangelists for the program inside the prison.

By the time Leal took part in The Last Mile in 2011, he had served 18 years of his sentence and was still looking at a minimum of 7 more years behind San Quentin’s walls. That was until just one year later, when California passed Proposition 36.

Under Proposition 36, prisoners serving a life-sentence under the three strikes rule for non-violent crimes became eligible for resentencing. Included in the 3,000 prisoners suddenly eligible for resentencing was Leal.

“I had to go back before the same judge who sentenced me to life in prison and demonstrate to him that I was no longer a danger to the community,” says Leal.

“I presented him with all of the information of the things that I had done while I was in prison to turn my life around. He reviewed it all and then he agreed to resentence me to seven years.”

Shortly after his resentencing, Kenyatta Leal walked out of San Quentin for good.

Ten days after his release Kenyatta got in touch with Duncan Logan, founder and CEO of San Francisco-based tech company Rocketspace, who he had met the year before through The Last Mile’s mentoring initiative.

Logan agreed to offer Kenyatta an internship at Rocketspace, which eventually over 4 years of hard work progressed into a full-time position as a team leader, a management role, and finally, a sales position.

Leal remained a part of the Rocketspace team until just three months ago, when he resigned to take up a full time development role at The Last Mile.

Expanding the Prison-To-Employment Pipeline

In his new capacity, Leal is helping The Last Mile to expand the reach of it’s program.

The program currently operates in 6 prisons across California and Indiana, half of which are women’s prisons.

The ambition however, is to expand to 500 prisons in just the next 10 years.

“It’s a really ambitious goal,” concedes Leal, “but we’re definitely on trajectory to meet that. We would like for The Last Mile to be ubiquitous with prison education.”

Not every state is going to be as easy to conquer as California has been, however. Leal acknowledges that many of the areas The Last Mile is hoping to expand into do not have the same resources and community as in Silicon Valley.

“Each state has different requirements and resources available. What we’re trying to do is go there and nurture those environments,” he explains. “We’re trying to reach out to people in the business community and create the kind of public-private partnership that’s necessary for a program like ours to work in those areas.”

Despite the challenges, Leal and the team at The Last Mile are confident that the program can work elsewhere. There’s even a similar program up and running in the UK, Code 4000, and the two regularly share their learnings with each other.

“It’s a little bit more difficult in some places, but I definitely think it’s possible” Leal concludes. “As challenging as it may be I also see it as a great opportunity and that’s what keeps me going every day.”

Missed the first part? Read the full series at https://medium.com/@DCDesign.

Working on these issues? Do get in touch with us at info@dcdesignltd.com and share your experiences, thoughts, perspectives. We’d love to hear from you.

Learn more about how we consult companies and government agencies on criminal justice, education, and more: www.dcdesignltd.com.